Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a condition caused by changes in a person’s genes. It makes muscles weak and gets worse over time. There are many types of muscular dystrophies, but DMD is the most common one. It affects how a protein called dystrophin is made in the body. This protein helps keep muscles strong and healthy. The condition usually starts showing symptoms when a child is young and affects specific groups of muscles.

Prevalence of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

This disease mostly affects boys, who are usually born with XY chromosomes. It’s very rare in girls with XX chromosomes. Globally, it occurs in less than 10 out of 100,000 boys at birth. Overall, dystrophy disorders affect around 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 6,000 boys at birth. The prevalence of this disease in India is estimated to be around 1 in every 3,500 to 5,000 male births. However, because of limited awareness, underdiagnosis, and lack of comprehensive data collection, the exact prevalence may vary across different regions of the country.

What Causes Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy?

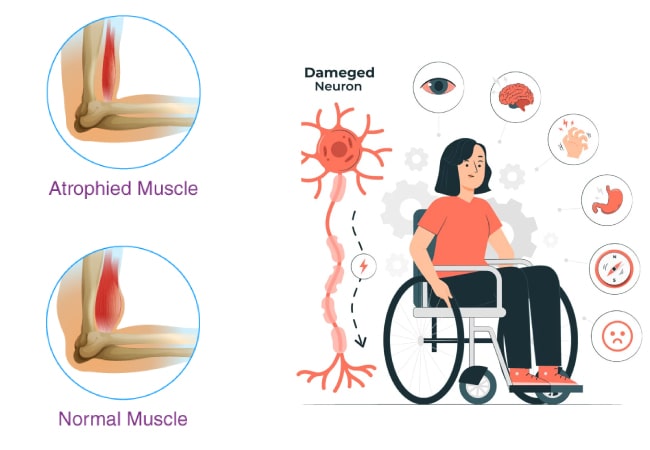

This inherited disorder arises from genetic mutations, either inherited or spontaneous, within the DMD gene. This gene, the largest known, encodes the dystrophin protein vital for muscle recovery post mechanical strain during movement. Mutations in DMD result in insufficient dystrophin production. Consequently, muscle cells become vulnerable, leading to degeneration and eventual loss of muscle function. Over time, the absence of dystrophin causes progressive muscle deterioration until complete functional impairment occurs.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Risk Factors:

The likelihood of inheriting Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy increases when individuals possess:

- A familial background of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) increases the likelihood of either inheriting the condition or being a carrier.

- In families with a carrier mother, there’s a 50% probability that male children with XY chromosomes will inherit the mutated gene, potentially leading to DMD.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Symptoms:

This inherited disorder typically manifests through a progressive decline in muscle strength and mass. Notably, individuals may develop enlarged calf muscles due to pseudohypertrophy, a result of fatty tissue replacing lost muscle cells. Additionally, cardiomyopathy, characterized by progressive enlargement of the heart, is a common feature of the disease.

Progression of DMD Symptoms: The condition is typically diagnosed in children between the ages of 2 and 11. During early childhood, signs of DMD may emerge, including walking on tiptoes, difficulty climbing stairs, clumsiness, weakness, and the use of hands to “walk” up their shins to stand, known as Gowers’ sign. These symptoms typically follow a predictable progression:

Childhood:

- Walking on toes

- Unusual or waddling walk

- Loss of certain reflexes

- Trouble climbing stairs

- Muscle weakness or atrophy affecting the upper extremities, pelvis, or thighs.

- Bulky muscles in other areas

- Muscle weakness that progresses to the trunk, neck, forearms, and lower legs

- Delayed ability to sit or stand without help

- Struggling to stand up from a seated or reclined position

- Frequent falls (especially when trying to run)

- Inability to jump or run

- Changes in the curvature of the spine

- Changes in the range of motion in joints

- As the diaphragm muscles lose strength, experiencing challenges with breathing ensues.

Adolescence and Teenage Years: During the initial stages of adolescence, the ability to walk diminishes in the majority of children with DMD, leading to the potential need for a wheelchair by ages 10 to 12. Additionally, various other changes may manifest, including:

- Reduced bone density

- Increased probability of fractures

- Subtle or moderate cognitive challenges or intellectual disabilities.

- Scoliosis

- Contractures, fixed stiffness in specific joints, may exacerbate with wheelchair usage.

- Possible adverse effects of long-term steroid therapies

- Weak diaphragm muscles due to respiratory issues

- Cardiomyopathy, a condition of the heart muscle

- Problems swallowing

Sometimes, between the ages of 3 and 6, children may experience temporary improvements in these aspects, yet subsequent muscular degeneration is common. By age 8 or 9, leg braces may be necessary for walking, particularly without physical therapy intervention.

Adulthood: In the initial stages of adulthood, individuals with DMD commonly confront notable respiratory and cardiac challenges, posing potential life-threatening risks. Typically, life expectancy for those with DMD averages in the mid- to late 20s.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Diagnosis:

Diagnosing DMD follows a structured approach, involving clinical evaluation, blood analysis, and genetic screening conducted by physicians.

Clinical Examination: Diagnosing DMD involves a comprehensive clinical examination, evaluating muscle strength, coordination, reflexes, and medical history. Vital signs are checked, and physical examination identifies any signs of inflammation or tenderness. Additional tests such as lab work or imaging may be ordered, followed by a possible referral to a specialist.

Blood and Urine Tests: Physicians suspecting Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) often order a creatine kinase (CK) test. CK, an enzyme found in muscle tissue, leaks into the bloodstream as muscle damage occurs. Typically, individuals without DMD have CK levels below 200 units per liter, while those with DMD may have levels 10 to 100 times higher. While a CK test indicates muscle issues, a DMD diagnosis requires further steps.

Genetic Tests: Genetic testing analyzes DNA samples to detect deletions, duplications, or single-point mutations in the DMD gene, aiding Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) diagnosis. PCR is commonly used for testing. It’s recommended for parents with a family history. Carrier screening helps identify mutations. Prenatal testing, like amniocentesis or CVS, can identify mutations in the fetus.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Treatment:

Treatment strategies for DMD concentrate on decelerating its advancement, addressing and mitigating symptoms and complications, and enhancing an individual’s quality of life (QoL).

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Therapies: Some treatments have demonstrated the ability to elevate functional dystrophin levels, albeit to a limited extent. Among these, a prevalent class of medications, known as “exon skipping” drugs, can aid certain patients in generating more beneficial dystrophin by bypassing problematic gene segments responsible for muscle protein complications.

Currently, exon-skipping therapies are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to target specific mutations in the dystrophin gene, including those amenable to exon 45, 51 (Exondys 51), or 53 skipping, for treating DMD patients.

Not all individuals with DMD benefit from these therapies. Only approximately 8%, 13%, and 8% of patients, respectively, find the three approved exon skippers effective.

Global Impact of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy:

The occurrence of the disease varies worldwide. In the United States, it affects approximately 1 assigned male live birth per 3,500. In Germany, DMD prevalence is as low as 1.5 per 100,000, contrasting with Italy’s higher rate of 28.2. In India, the prevalence varies, but it is estimated to occur in approximately 1 in every 5,000 to 6,000 male births.

Reference:

https://www.mda.org/disease/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy

https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6291/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy

https://www.musculardystrophyuk.org/conditions/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-dmd

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482346/#:~:text=Duchenne%20muscular%20dystrophy%20(DMD)%20is%20one%20of%20the%20most%20severe,muscle%20fiber%20degeneration%20and%20weakness.